William [‘Billy’] La Touche Congreve VC, DSO, MC – a Burton Hero

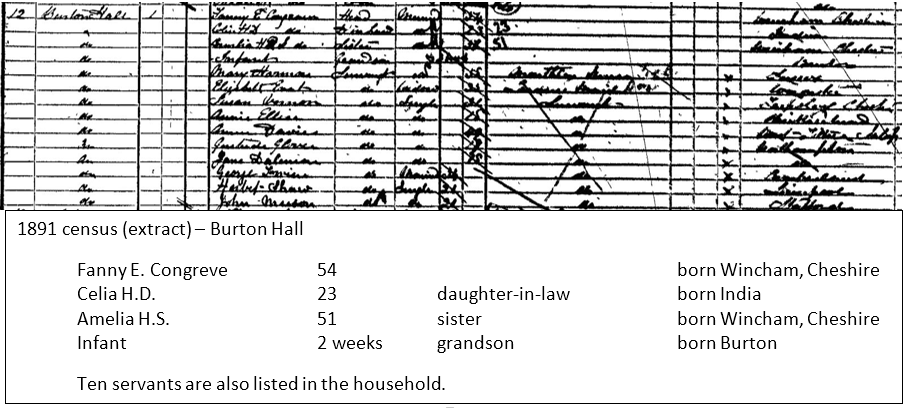

by Ian L. Norris [This is an abstract from a more detailed account of Billy Congreve and his family which will, alongside detailed accounts of the other known World War 1 fatalities of Burton and Neston, see HomeTown Heroes pages] In stark contrast to many of the Burton and Neston First World War casualties a considerable amount is known and recorded about the life, and death, of ‘Billy’ Congreve and his family and so only the barest outlines will be given here. Early Years William La Touche Congreve was born on 22 March 1891 at Burton Hall, the Congreve family home and the predecessor of Burton Manor when rebuilt after 1903 by Henry Neville Gladstone. His middle name, La Touche, was after his mother’s maiden name – she was Cecilia (Celia) Henrietta Dolores Blount La Touche. William’s father, Captain Walter Norris Congreve (later General) was a distinguished soldier in the Second Boer War [The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own)] when, in December 1899, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.  At the time of the 1891 census (5 April) Billy was just two weeks old, unnamed (and shown as ‘infant’ in the census return) and with his mother at Burton Hall. Fanny Emma Congreve (nee Townshend, of Wincham Hall near Northwich) was the head of household on that date; Billy’s grandmother, she was the wife of William [‘The Captain’] Congreve although William was, as was commonly the case, away from the village at that time. Also absent from the Hall was Billy’s father, Walter Norris Congreve; it is presumed that he had returned to his army regiment – around this time he was Assistant Adjutant for Musketry stationed at Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight. Whilst Billy Congreve was born in Burton, and spent some of his early time in the village, the family lived away from the area for considerable periods as his father’s army work (for some time he was private secretary to Lord Kitchener) took him around the country. Indeed, at the time of the 1901 census the family was fragmented with Billy (10, a pupil) being recorded at the home of 49-year old school mistress Sara Linton in Farnborough. It is possible that Billy was in Farnborough to visit his father, Walter Norris Congreve, as he might have been in Britain at that time after his actions in the Second Boer War and his award of the Victoria Cross (although he cannot be located in the census returns). Certainly, whilst Billy was in Farnborough his mother, Celia (33, born India) together with Billy’s younger brother, Geoffrey Cecil Congreve, was with her mother and step-father in Sevenoaks, Kent. Celia’s mother, Rosa, had married Charles W. Blount La Touche, a Captain in the Indian Army, at St James’ Westminster in mid-1866. Following their marriage Charles and Rosa went back to India but Charles died the following year (29 December1867) in Macherber Kattywar, India, and Cecilia [Celia] Henrietta Dolores La Touche, their only child, was born shortly before Charles died. Charles had served with distinction in India during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and had been recommended for the VC, although this was not awarded. Had it been granted Cecilia would have had the unique distinction of being the daughter, wife and mother of holders of the VC. William [‘The Captain’] Congreve, Billy Congreve’s grandfather, had been the Chief Constable of Staffordshire (and lived in Stafford) when he retired to Burton Hall in 1889.

At the time of the 1891 census (5 April) Billy was just two weeks old, unnamed (and shown as ‘infant’ in the census return) and with his mother at Burton Hall. Fanny Emma Congreve (nee Townshend, of Wincham Hall near Northwich) was the head of household on that date; Billy’s grandmother, she was the wife of William [‘The Captain’] Congreve although William was, as was commonly the case, away from the village at that time. Also absent from the Hall was Billy’s father, Walter Norris Congreve; it is presumed that he had returned to his army regiment – around this time he was Assistant Adjutant for Musketry stationed at Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight. Whilst Billy Congreve was born in Burton, and spent some of his early time in the village, the family lived away from the area for considerable periods as his father’s army work (for some time he was private secretary to Lord Kitchener) took him around the country. Indeed, at the time of the 1901 census the family was fragmented with Billy (10, a pupil) being recorded at the home of 49-year old school mistress Sara Linton in Farnborough. It is possible that Billy was in Farnborough to visit his father, Walter Norris Congreve, as he might have been in Britain at that time after his actions in the Second Boer War and his award of the Victoria Cross (although he cannot be located in the census returns). Certainly, whilst Billy was in Farnborough his mother, Celia (33, born India) together with Billy’s younger brother, Geoffrey Cecil Congreve, was with her mother and step-father in Sevenoaks, Kent. Celia’s mother, Rosa, had married Charles W. Blount La Touche, a Captain in the Indian Army, at St James’ Westminster in mid-1866. Following their marriage Charles and Rosa went back to India but Charles died the following year (29 December1867) in Macherber Kattywar, India, and Cecilia [Celia] Henrietta Dolores La Touche, their only child, was born shortly before Charles died. Charles had served with distinction in India during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and had been recommended for the VC, although this was not awarded. Had it been granted Cecilia would have had the unique distinction of being the daughter, wife and mother of holders of the VC. William [‘The Captain’] Congreve, Billy Congreve’s grandfather, had been the Chief Constable of Staffordshire (and lived in Stafford) when he retired to Burton Hall in 1889.

In the 1901 census he is recorded there, aged 69, with his wife Fanny Emma (64) and two daughters (Winifred Mary Congreve, 28, and Dorothy Lee King, 26). Despite having not lived in Burton for most of his tenure of the village (Burton Hall had been leased to a succession of tenants), William had invested considerable amounts in the village and this had adversely affected the wealth of the family. On William Congreve’s death in January 1902 Burton Hall, and the village, passed to his eldest son, Major Walter Norris Congreve, Billy Congreve’s father. Walter heard of his father’s death at the time that he was serving as private secretary to Lord Kitchener in the Transvaal (South Africa). On his return to Britain, and wishing to rid himself of the financial burden of Burton, Walter put the entire Burton estate up for sale and it was sold to Henry Neville Gladstone for £80 000 on 2 February 1903, just 13 months after The Captain’s death and just a few weeks short of Billy Congreve’s 12th birthday. The family then moved to Ireland – Walter had obtained the post of personal assistant (Aide-de-camp) to the Duke of Connaught – but Walter, requiring a home in England, purchased Chartley Castle in Staffordshire in September 1904. Billy Congreve, a somewhat sickly child, was sent away to school at an early age, firstly to Summer Fields School, Oxford and then to Eton College, (1904 -1907) where he was considered to be an ‘average’ scholar. Following Eton he attended a crammer in London and won a place at Sandhurst, then the Royal Military College, in Surrey. Billy was at the RMC, as a ‘Gentleman Cadet Sergeant’, from1909 until 1911; here he excelled and nearly won the Sword of Honour, coming second in his entry [The Sword of Honour is awarded to the British Army Officer Cadet considered by the Commandant to be, overall, the best of the course]. The Army Leaving the RMC in 1911 Billy obtained a commission in the 2nd Light Rifle Brigade on 4 March and, in the same year, was posted to the 3rd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade in Tipperary where he spent three years. On 1 February 1913 he was promoted to Lieutenant. However, at the time of the 1911 census Billy was with his parents and younger brother Christopher at their military home in Kent, Commandant House, which was adjacent to Hythe Barracks:  Also in the household were five servants and one visitor. Walter and Cecilia had been married for 20 years and all three children had survived.

Also in the household were five servants and one visitor. Walter and Cecilia had been married for 20 years and all three children had survived.  With the outbreak of the Great War Billy’s battalion was sent to France where he was soon appointed (2 November 1914) to the staff position of Aide de Camp to major-general Hubert Hamilton. Such positions – well behind the front line – were considered ‘safe’ and these officers were mostly despised by the fighting soldiers. It would turn out, however, that Billy did not wish to lead from a position of safety but (and this is portrayed graphically through his diaries) wished at all times to have a direct involvement in leading from the front. Billy’s first significant encounter with the enemy was at the 1914 battle of Neuve-Chapelle where, having installed himself in a house overlooking the frontline trench, he saw how the attack of the Indian troops failed and how the whole involvement was going badly wrong. At one point Billy and his friend Cornwall (both only Lieutenants) took over the control of the reserve Battalions because they were retiring:

With the outbreak of the Great War Billy’s battalion was sent to France where he was soon appointed (2 November 1914) to the staff position of Aide de Camp to major-general Hubert Hamilton. Such positions – well behind the front line – were considered ‘safe’ and these officers were mostly despised by the fighting soldiers. It would turn out, however, that Billy did not wish to lead from a position of safety but (and this is portrayed graphically through his diaries) wished at all times to have a direct involvement in leading from the front. Billy’s first significant encounter with the enemy was at the 1914 battle of Neuve-Chapelle where, having installed himself in a house overlooking the frontline trench, he saw how the attack of the Indian troops failed and how the whole involvement was going badly wrong. At one point Billy and his friend Cornwall (both only Lieutenants) took over the control of the reserve Battalions because they were retiring:

It was getting dark now, and when I got to Pont Logy I found to my horror that the Bedfords and Cheshires were retiring, goodness only knows why. I felt inclined to sit down and cry, but hadn’t time. The men said that they had had orders to retire. There were very few officers about and what there were seemed useless. The officer commanding – a captain – saluted me and called me ‘Sir’, which showed he was pretty far gone. Eventually Cornwall and I, after great efforts, got them together and started them digging…….. As we stood on the road (it was almost dark), a German machine-gun opened fire down the road …that cleared us off in no time.

Billy’s most momentous military actions, marriage and death, all occurred in the last few months of 1915 and first 7 months of 1916; this is the outline of the events of that short period. On 18 August 1915 Billy, still a Lieutenant was appointed as a General Staff Officer (GSO) 3rd Grade and on 3 September he was promoted to Captain. During September and October 1915 Billy Congreve’s 3rd Division was involved in the huge combined-armies operation around Hooge which, if all had gone according to plan, would result in the British meeting with the French armies and pushing northwards towards Belgium. This, however, turned out to be a fiasco and resulted in great loss of life, but for his actions Billy was awarded the Military Cross (awarded 11 Jan 1916). On 8 December 1915 Billy Congreve was appointed brigade-major to the 76th Brigade (3rd Division)[the post he held when he was killed] and, on 22 February 1916, he was awarded the Legion of Honour Croix de Chevalier. On 16 May 1916 Billy Congreve was awarded the DSO and on 13 June was Mentioned in Despatches. On 27 March 1916 an attack near St. Eloi in heavy mist led to Billy, then just 25, gaining his next military award. An unknown number of Germans, positioned in a large shell crater, were under attack and were returning the British fire. Billy noticed that, although their firing was continuing, a sandbag had been hoisted on a stick and was being waved about by some of the Germans. Concluding that at least some of the Germans were willing to surrender Billy thought that bluff might work so, instructing a nearby officer and four men to follow him, Billy dashed for the crater waving his revolver in the air. Although fired upon Billy wasn’t hit and, on reaching the rim of the crater and looking in:

Imagine my surprise and horror when I saw a whole crowd of armed Boches! I stood there for a moment feeling a bit sort of shy, and then Ievelled my revolver at the nearest Boche and shouted, ‘Hands up, all the lot of you!’ few went up at once, then a few more and then the lot; and I felt the proudest fellow in the world as I cursed them.

It turned out he had captured 4 officers and 68 men and, although recommended for the Victoria Cross, Billy was awarded the DSO for this action. Two months later Billy returned to Britain on leave and, on 1 June 1916, he married his long-time girlfriend and actress, Pamela Cynthia Maude, at St Martin’s-in-the-Fields. Mid-1916 had been designated as the time for a major combined offensive and so, after just a few days of honeymoon, Billy rejoined his brigade at Meteren. Around this time Billy’s father, Walter Norris Congreve, was serving on the front line and many instances are recorded when, in the battlefield area, father and son met to discuss the war. Indeed, on one occasion Billy’s youngest brother, Christopher John, then aged only 12 (during a school holiday and dressed in his Boy Scout’s uniform) visited Billy on the front line. Killed in Action On Thursday 20 July 1916 the fighting to capture the area around Longueval and Delville Wood was the main priority and two battalions of Billy’s 76th Brigade (X111 Corps., 3rd Division) were involved, the 2nd Suffolks and the 10th Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF). The Suffolks began their advance from the westerly direction at 3.35 am and the RWF failed to make contact as they were led astray by guides who lost their way. The Suffolks went on unsupported and and the two leading companies were decimated. When the 10th Royal Welch Fusiliers did finally arrive they were mistakenly fired on by a machine-gun barrage from the 11th Essex battalion in which they lost many of their officers. It was this mess that Congreve was attempting to sort out when, talking to Major Stubbs at the Suffolks H.Q. and making notes of the situation, he was shot in the throat by a sniper as he was climbing down from the top of a disused gunpit. The time of death was 10.55am; he was aged 25 years, 4 months and 8 days. The following day Congreve’s body was taken to the nearby town of Corbie and his father, who had heard of his son’s death but still had to attend a Fourth Army Conference that morning, afterwards visited his body. For his actions at this time Billy was awarded the VC posthumously and his citation sums up this award. It is generally recognised that if Billy had survived the Great War that he would have been one of Britain’s military leaders during WW2.

Mid-1916 had been designated as the time for a major combined offensive and so, after just a few days of honeymoon, Billy rejoined his brigade at Meteren. Around this time Billy’s father, Walter Norris Congreve, was serving on the front line and many instances are recorded when, in the battlefield area, father and son met to discuss the war. Indeed, on one occasion Billy’s youngest brother, Christopher John, then aged only 12 (during a school holiday and dressed in his Boy Scout’s uniform) visited Billy on the front line. Killed in Action On Thursday 20 July 1916 the fighting to capture the area around Longueval and Delville Wood was the main priority and two battalions of Billy’s 76th Brigade (X111 Corps., 3rd Division) were involved, the 2nd Suffolks and the 10th Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF). The Suffolks began their advance from the westerly direction at 3.35 am and the RWF failed to make contact as they were led astray by guides who lost their way. The Suffolks went on unsupported and and the two leading companies were decimated. When the 10th Royal Welch Fusiliers did finally arrive they were mistakenly fired on by a machine-gun barrage from the 11th Essex battalion in which they lost many of their officers. It was this mess that Congreve was attempting to sort out when, talking to Major Stubbs at the Suffolks H.Q. and making notes of the situation, he was shot in the throat by a sniper as he was climbing down from the top of a disused gunpit. The time of death was 10.55am; he was aged 25 years, 4 months and 8 days. The following day Congreve’s body was taken to the nearby town of Corbie and his father, who had heard of his son’s death but still had to attend a Fourth Army Conference that morning, afterwards visited his body. For his actions at this time Billy was awarded the VC posthumously and his citation sums up this award. It is generally recognised that if Billy had survived the Great War that he would have been one of Britain’s military leaders during WW2.

Citation An extract from the London Gazette, dated 24th October, 1916 records the following: “For most conspicuous bravery during a period of fourteen days preceding his death in action. This officer constantly performed acts of gallantry and showed the greatest devotion to duty, and by his personal example inspired all those around him with confidence at critical periods of the operations. During preliminary preparations for the attack he carried out personal reconnaissances of the enemy lines, taking out parties of officers and non- commissioned officers for over 1,000 yards in front of our line, in order to acquaint them with the ground. All these preparations were made under fire. Later, by night, Major Congreve conducted a battalion to its position of employment, afterwards returning to it to ascertain the situation after assault. He established himself in an exposed forward position from where he successfully observed the enemy, and gave orders necessary to drive them from their position. Two days later, when Brigade Headquarters was heavily shelled and many casualties resulted, he went out and assisted the medical officer to remove the wounded to places of safety, although he was himself suffering severely from gas and other shell effects. He again on a subsequent occasion showed supreme courage in tending wounded under heavy shell fire. He finally returned to the front line to ascertain the situation after an unsuccessful attack, and whilst in the act of writing his report, was shot and killed instantly.”

The red line marks the main British front line, the orange arrows the direction of attack and the purple circle the opening position of the 3rd Division. Billy Congreve was shot by the trench/road known as Duke Street; this position is identified by the symbol ![]()

Billy’s widow, Pamela, had been married to Billy for only 7 weeks before he was killed and, on 21 March 1917 she gave birth to their daughter, Mary Gloria Congreve. On 21 July 1916 ‘Billy’ La Touche Congreve was buried at Corbie Communal Cemetery and, on 1 November 1916, his widow received her husband’s medals from the King at Buckingham Palace. Billy Congreve was the first officer in the Great War to earn all three medals, the VC, DSO and MC and was mentioned in despatches on 5 occasions. Had he been awarded the VC when he was first recommended for this, in March 1916 (when, instead, he was awarded the DSO), he would have had the honour of gaining the VC and bar. A fellow officer commented:

Billy’s widow, Pamela, had been married to Billy for only 7 weeks before he was killed and, on 21 March 1917 she gave birth to their daughter, Mary Gloria Congreve. On 21 July 1916 ‘Billy’ La Touche Congreve was buried at Corbie Communal Cemetery and, on 1 November 1916, his widow received her husband’s medals from the King at Buckingham Palace. Billy Congreve was the first officer in the Great War to earn all three medals, the VC, DSO and MC and was mentioned in despatches on 5 occasions. Had he been awarded the VC when he was first recommended for this, in March 1916 (when, instead, he was awarded the DSO), he would have had the honour of gaining the VC and bar. A fellow officer commented:

I don’t think there was ever anyone like him; he was absolutely glorious, and even when he was ADC, all the men knew and loved him -which is unusual. His friendship has done more for me in many ways than I can say; it was the most priceless thing I had. He was the bravest and most gentle fellow in the world, and I can imagine the smile with which he greeted the ‘sudden turn’ when the bullet got him.

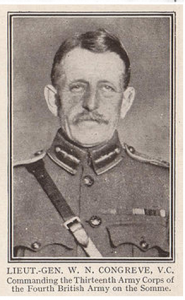

A Postscript : Walter Norris Congreve  Walter Norris Congreve, the father of Billy Congreve (and Geoffrey Cecil and Arthur Christopher John Congreve, who also achieved notable military careers) had served with distinction in the Second Boer War in South Africa where, in December 1899, he was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Colenso during the Relief of Ladysmith. Early in July 1914, in talking to a friend, he remarked that he was not likely to achieve anything more important in the army (he was then 52) than the Command of an Infantry Brigade. However, on the outbreak of WW1 Walter Congreve’s Brigade was ordered to mobilise and in September 1914 he and his 18th Infantry Brigade were sent to France and Belgium to get front-line experience. In 1915 he was promoted to Major-General and, in July 1916, was in action when he heard that his son ‘Billy’ had been killed. In the middle of June 1917 Congreve was severely wounded by a shell at the foot of the Vimy Ridge; his left hand was almost completely blown off by shrapnel and had to be amputated. Later, he had an iron hook fitted. In 1917 he returned home, in fairly poor health, to Chartley – he had returned to the family homeland of Staffordshire having sold Burton to Henry Neville Gladstone – and was created a KCB. Promoted to Lieutenant-General, in January 1918, for services in the field, Walter Norris Congreve returned to command the V11 Corps (part of the 5th Army, commanded by General Sir Hubert Gough) in France. Still in poor health, he transferred to the Command of the X Corps, resting near Crecy, and remained there until the end of the war. In August 1919, and still in poor health, Congreve went to Palestine as Commander of the North Force of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and, in October 1919, he became G.O.C. of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force – he now commanded all the troops in Egypt and Palestine except the Egyptian Army. Returning to England in 1923 (Congreve was now a full General and Colonel-Commandant, he became a Brigadier-General and Aide-de-Camp to King George v. On 29 June 1925 he took up his final post when he became Governor of Malta. It was in Malta, in February 1927, after a distinguished army career in two wars that Walter Norris Congreve VC KCB KSA died and, with full military honours, was buried at sea off the island. The Victoria Cross was created on 29 January 1856 and it is understood that it has been awarded 1358 times, 628 of these awards being during the First World War. Three fathers and sons have earned the Victoria Cross: Major Charles Gough in 1857 and his son Major John Gough in 1903; Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (1858) and his son Lieutenant (1899); and Walter Norris Congreve (1899) and Billy (1916). Indeed, Walter Norris Congreve and Freddie Roberts were close friends and both gained the VC at the same action at Colenso, although Freddie died of wounds two days later and so received his award posthumously. Burton village was the family home from around 1806 until the sale of the village to Henry Neville Gladstone in 1903, and the birthplace in March 1891 of Billy Congreve. On 20th July 2016 a commemorative event was organised at the Village Hall to mark the centenary of his death…click here for a full account

Walter Norris Congreve, the father of Billy Congreve (and Geoffrey Cecil and Arthur Christopher John Congreve, who also achieved notable military careers) had served with distinction in the Second Boer War in South Africa where, in December 1899, he was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at Colenso during the Relief of Ladysmith. Early in July 1914, in talking to a friend, he remarked that he was not likely to achieve anything more important in the army (he was then 52) than the Command of an Infantry Brigade. However, on the outbreak of WW1 Walter Congreve’s Brigade was ordered to mobilise and in September 1914 he and his 18th Infantry Brigade were sent to France and Belgium to get front-line experience. In 1915 he was promoted to Major-General and, in July 1916, was in action when he heard that his son ‘Billy’ had been killed. In the middle of June 1917 Congreve was severely wounded by a shell at the foot of the Vimy Ridge; his left hand was almost completely blown off by shrapnel and had to be amputated. Later, he had an iron hook fitted. In 1917 he returned home, in fairly poor health, to Chartley – he had returned to the family homeland of Staffordshire having sold Burton to Henry Neville Gladstone – and was created a KCB. Promoted to Lieutenant-General, in January 1918, for services in the field, Walter Norris Congreve returned to command the V11 Corps (part of the 5th Army, commanded by General Sir Hubert Gough) in France. Still in poor health, he transferred to the Command of the X Corps, resting near Crecy, and remained there until the end of the war. In August 1919, and still in poor health, Congreve went to Palestine as Commander of the North Force of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and, in October 1919, he became G.O.C. of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force – he now commanded all the troops in Egypt and Palestine except the Egyptian Army. Returning to England in 1923 (Congreve was now a full General and Colonel-Commandant, he became a Brigadier-General and Aide-de-Camp to King George v. On 29 June 1925 he took up his final post when he became Governor of Malta. It was in Malta, in February 1927, after a distinguished army career in two wars that Walter Norris Congreve VC KCB KSA died and, with full military honours, was buried at sea off the island. The Victoria Cross was created on 29 January 1856 and it is understood that it has been awarded 1358 times, 628 of these awards being during the First World War. Three fathers and sons have earned the Victoria Cross: Major Charles Gough in 1857 and his son Major John Gough in 1903; Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (1858) and his son Lieutenant (1899); and Walter Norris Congreve (1899) and Billy (1916). Indeed, Walter Norris Congreve and Freddie Roberts were close friends and both gained the VC at the same action at Colenso, although Freddie died of wounds two days later and so received his award posthumously. Burton village was the family home from around 1806 until the sale of the village to Henry Neville Gladstone in 1903, and the birthplace in March 1891 of Billy Congreve. On 20th July 2016 a commemorative event was organised at the Village Hall to mark the centenary of his death…click here for a full account